Calligraphy is one of the most important genres of art in China. Historically the Chinese have regarded calligraphy as a unique expression of scholarship, character, and cultural attainment, and as a sublime art form. (Even though Chinese calligraphy can be practiced as a hobby, Chinese people never consider calligraphy as a "craft.")

The earliest extant examples of Chinese writing are the inscriptions that appear on so-called oracle bones (animal bones and turtle shells) and on bronze vessels, the oldest of which date back to the Shang Dynasty. The kings of the Shang Dynasty used these objects in important divination rituals, and some scholars have argued that this early association of writing with ritual and political authority helps to account for the special status conferred upon those who could read and write.

These early inscriptions were made on the surface of an oracle bone or a bronze mold with a sharp and pointed instrument such as a knife. Before the molding, the scripts were written with brushes and ink in most cases. As a result of these processes, the Chinese characters (or "pictographs" as they are also called, but not symbols) were already rich in emotions and variations in brushstrokes and other attributes. Serious studies point out that Chinese calligraphy was born as the same time as the Chinese characters were invented or evolved. (Some sources state that the Oracle Bone and Bronze Inscriptions generally lack the kinds of linear variation and other attributes to be considered true Chinese calligraphy. This is very misleading and incorrect! In fact, many great Chinese calligraphers spend tremendous amount of time studying and emulating the Seal Style calligraphy of the Oracle Bone and Bronze Inscriptions, especially the latter. They regard those early scripts as "mature" paradigms and "paramount" models to practice Seal Style calligraphy.)

Chinese characters have a long history of evolutions. Records of formal Chinese writings date back more than 3300 years to the Shang and Zhou Dynasties. The development and spread of writing, driven by progress and growing requirements of society and the introduction of brush and ink, set the stage for the gradual evolution of the unique art of Chinese writing.

Oracle Bone Inscription, c. 1300 BC

Readers may visit the following websites to enhance their understanding about Oracle Bone Inscriptions and Bronze Inscriptions (Jin Wen):

![]() http://www.chinavista.com/experience/oracle/oracle.html

http://www.chinavista.com/experience/oracle/oracle.html

![]() http://www.cse.cuhk.edu.hk/~irg/irg/irg24/IRGN1119Old_Hanzi_Oracle_PRC.pdf

http://www.cse.cuhk.edu.hk/~irg/irg/irg24/IRGN1119Old_Hanzi_Oracle_PRC.pdf

![]() http://www.erols.com/bcccsbs/chisacw.htm

http://www.erols.com/bcccsbs/chisacw.htm

![]() http://www.indiana.edu/~libeast/oracle.html

http://www.indiana.edu/~libeast/oracle.html

![]() http://www.npm.gov.tw/english/index-e.htm

http://www.npm.gov.tw/english/index-e.htm

![]() http://www.ucpress.edu/books/pages/9394.html

http://www.ucpress.edu/books/pages/9394.html

("Reading the Past Chinese" written by Dr. Oliver Moore)

Chinese calligraphy is an art of strokes and structures of Chinese characters, and over the centuries, different styles and scripts have been developed. From the elaborate, pictographic character and the Seal Script to the spontaneous exuberance of the Cursive Script, strokes, dots and expressions are laid down to form complex pictures of abstract beauty. Ink flows out of the Chinese brushes like notes of music, floating with cadence in a stream of intertwined rhythm and melody. The composition takes on a life of its own and attracts the viewers, even though the viewers may not understand the Chinese language and the meanings of the calligraphic writing.

|

|

|

|

Clerical Style, Tsao Chuan Tablet in Han Dynasty |

Clerical

Style, Hsien Yu Huan Tablet in Han

Dynasty |

The evolution of Chinese calligraphy has often been influenced by

political and social conditions. In the Wei and Jin Dynasties, as well as the

Northern and Southern Dynasties, the chaos of the times contributed to the rise

and popularity of the "metaphysical conversations ( 清

談 )." As the literati labored to cast off the yoke of

the Confucian ethical code of the Han Dynasty, there was more space for bold

imagination in the arts, and great masters of calligraphy, such as Wang

Hsi-Chih, gained prominence and won the title of the "Calligrapher-Sage

( 書

聖 )." Later, amidst the literary and military

accomplishments of the Tang Dynasty, calligraphy became part of the imperial

examinations, and famous court ministers such as Yu

Shih-Nan and Zu Suei-Liang were also renowned

as calligraphers who were highly trusted and regarded by the emperors. Even today, over a thousand years later, the art and literary

works of the Tang Dynasty still evoke the literary magnificence of the ancient

capital city Chang-An.

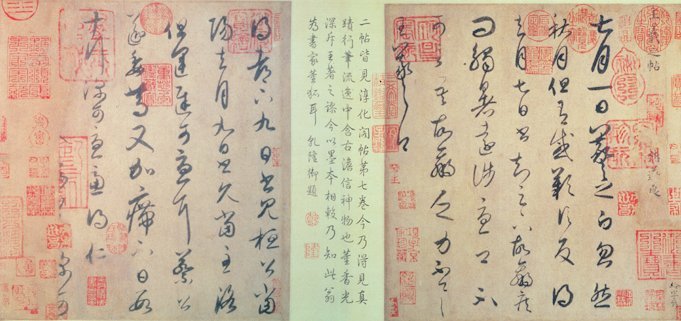

Running & Walking Styles by Wang Hsi-Chih, 321-379

Walking & Running Styles by Wang Hsian-Chih (7th Son of Wang Hsi-Chih), 344-388

Through calligraphy, Chinese intellectuals gave form to individual thoughts, personal morals, virtues, and innermost sentiments. In the works of ancient masters, we can see the calligraphers' personalities at work: the unrestrained freedom of Wang Hsi-Chih, the graceful, upright style of General Yen Jen-Ching, the unruly indulgence of the monk Huai Su, the easy flow of emotion and talent of Su Shu, and the elegance and delicate beauty of Emperor Huei-Zong of the Sung Dynasty, and etc.

|

|

|

|

Standard Style, Monument of Zen Master Guei-Fon in Tang Dynasty |

Standard

Style, Heart

Sutra by Ou-Yang

Shuen in Tang Dynasty |

Golden Skinny Style by Emperor Huei-Zong

in Sung Dynasty

(http://www.npm.gov.tw/masterpiece/enlargement.jsp?pic=C2B000001)

|

|

Affection and respect for the written characters and paper are instilled from childhood in the Chinese heart. In many towns and villages of China and Taiwan, there are still "Pagodas of Compassionating the Characters ( 惜字亭 )" built for the burning of waste paper bearing writing. For we Chinese respect characters so highly that we cannot bear them to be trampled under foot or thrown away into distasteful places. Decades ago, it was common to see men carrying waste paper with plaited bamboo baskets to the pagodas for burning. Respecting our written characters also came from the teachings of Confucianism. Those pagodas are also called "Pagodas of Respecting the Characters ( 敬字亭 )," "Pagodas of Respecting the Saints ( 敬聖亭 )," or "Pagodas of Hallowing Confucius ( 孔聖亭 )."

|