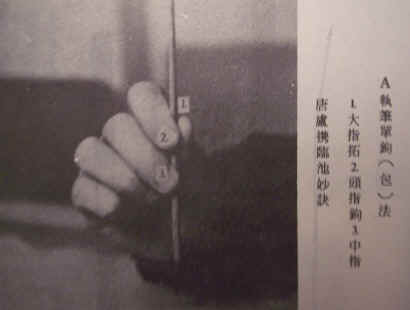

Single Hook Method

|

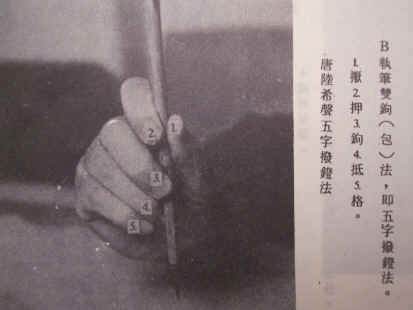

Double Hook Method

|

Principles of Chinese Calligraphy

P2: How to Hold a Brush 執筆之道﹕施於物、應於物、生於物,走轉隨化,知止圓融。

There are many different methods of holding a Chinese calligraphy brush among Chinese calligraphers and common people. They may be different for various Chinese calligraphy styles in different sizes. The principles may be somewhat different and some remain to be secrets. It's very common for calligraphers to disagree or agree with others' methods. A few of them had revealed their secrets by publishing their methods and theories. Most of the main principles will be similar - the most common principle is to keep fingers solid (i.e., hold the brush firmly) and leave emptiness inside the palm ( 指實掌虛 ). ( 唐太宗曰:指實則筋力均平,掌虛則運用便易。)

A video covering Brush Holding Methods before taller tables and chairs were introduced to China

( 百家講壇 書法檔案 3 蘇東坡:執筆無定法 )

Though every calligraphy master has his own way of handling his brush, a beginner must first follow some basic rules. The brush must be hold absolutely or nearly vertically, inclining neither sideways nor toward one self. Operating the brush toward one self (especially when doing a long vertical stroke) is the most commonly seen mistake - even among the so-called Chinese calligraphers.

Like fingerings on the piano, our fingers should or should not be in certain positions and angles when holding a brush. Our fingers may or may not be in certain positions and angles to create certain desired effects or avoid some contingencies. The correct ways of holding a brush play a vital role in one's achievements in learning Chinese calligraphy.

Here are some of the methods of holding Chinese calligraphy brushes from Chinese Websites after searching "執筆法" from Google.

http://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MjM5NTI1MTU1NA==&mid=200155786&idx=2&sn=a35c9e0cb43f9fda4401b717e18cf40f

http://www.ruyangliu.com/html/mbwh/gyb/1174.html

http://www.360doc.com/content/13/0106/12/5446466_258530929.shtml

http://www.douban.com/group/topic/50833790/

§ 2.1 – Conventional Methods

Generally, all five fingers will be used to hold a brush and each finger will have direct and indirect effects in writing. If a certain finger is not used, a stroke will look different from the other strokes when that finger is used.

Generally the thumb and the second and third fingers should grasp the handle, with the fourth (and fifth) finger(s) being placed directly on the brush handle to neutralize and balance the excessive force of the first three fingers. The essential for beginners is to let the strength of wrist and arm flow into the strokes through the brush hair. An important point to remember is not to let the strength of each individual finger "offset" one another. It's all about "balance" and "coordination" - not merely offset or counteract. Try to leave minimal gaps between the second, third, fourth, and fifth fingers. Generally, the gaps should not be more than 0.5 cm, otherwise the forces generated by each finger will be isolated.

There are some inferior methods of holding the brush. One of the most commonly seen methods is placing the index finger in an extremely high position. If the index finger is placed too far away from the middle finger with the wrist overstrained, it may form an angular shape for the knuckles of the index finger. The index finger may become overly tense or loose and its function in operating the brush is restrained, unless the writer has very flexible joints. (Hint: Feel the horizontal and vertical forces by our fingers, palm, wrist, and arm. And then find a good position for our hands that can balance the horizontal and vertical strengths to be applied to beautiful and smooth writing.)

In order to achieve the best ergonomics in practicing Chinese calligraphy, the following basic principles should be observed by the beginners.

1. Empty the fist and keep the inside of palm round ( 掌虛 ) as if we can hold a small egg.

The

benefits of keeping the Tiger Mouth round may be realized when one practices

smaller size calligraphy in cursive style and writes curved strokes in faster

speeds.

2. Keep the fingers firm ( 指實 ) and use the fingertips instead of knuckles to hold the brush.

3. Level the wrist to a more natural and horizontal angle and avoid strained angles.

4. Keep the brush upright. The technique or principle is called "round stroke" or "upright stroke."

5. Keep the wrist supple, firm, and soft. Do not tighten up the wrist.

|

|

Click to read an adapted Chinese article: Article 1

§ 2.2 – Bao’s Methods

In the Ching Dynasty, Bao Shichen ( 包世臣,1775-1855) published a famous calligraphy book Yi Zou Shuang Ji ( 藝舟雙輯 ). His deep admiration for his teacher Deng Shiru ( 鄧石如 ) and his methods gave a revelation to later calligraphers such as Wu Rangzhi ( 吳讓之 ) and Zhao Zhiqian ( 趙之謙 ). In this book, Bao emphasized the importance of holding a brush as adopted by Deng Shiru.

Bao Shichen's Famous Methods of Holding A Brush:

§ 2.3 – Correct and Incorrect Methods

Many incorrect and inferior ways of holding a brush have been published, taught, and adopted by so-called Chinese calligraphers and handed down to the beginners or even Westerners who have limited knowledge about Chinese calligraphy. Today many people don’t emphasize the correct ways to hold a brush seriously. It’s sad that many of them never spend time to study the various correct ways of holding a brush. They learn the way “as taught” or “as shown” but not “as it was or should be by ancient Chinese calligraphy masters.” Eventually most students don’t care the correct or more effective and efficient ways to hold and use a brush. This is one of the reasons why the levels of Chinese calligraphers are lower compared with ancient times.

|

A correct way to hold a brush |

Incorrect – brush should be vertical |

Incorrect – wrist tightened |

§ 2.4 - Three-Fingers Method

There is another rare school of holding a brush that is not commonly published in books or known to the general public. They emphasize on using only three fingers. The reasoning is based on the assumption that if fewer fingers are used one can concentrate more easily.

This method is used mostly when one is

using the Hanging Arm Technique ( 懸肘

) - holding the brush with the whole arm hanging in the air;

the elbow, wrist, and hand must not rest on the desk. This method was widely used in the pre-Chin Dynasty periods for

Zhuan Shu writing.

The Three-Fingers Method ( 三指法

) insists on using fingertips to hold the brush instead of using knuckles. Many calligraphers in the Ching Dynasty used five-fingers methods that let them rotate the brush with knuckles when necessary in writing a stroke. They admitted if they rotated the brush too much it would fall onto the ground. It has advantages and disadvantages. The Three-Fingers Method has its limitation in rotating the brush to a wider range since it requires the use of fingertips. (In ancient times before the Han Dynasty, writings were much smaller than they were in later dynasties. So calligraphers could easily rotate the brush if necessary because the characters and strokes were also smaller. Papers were not invented or were very expensive in

earlier times.)

|

Hanging Arm Technique ( 懸肘 ) with Five Fingers

|

Hanging Arm Technique ( 懸肘 ) with Three Fingers

|

There are more sensitive nerves in the fingertips than in the knuckles. This is one of the reasons that makes it easier to focus by using the fingertips. By adopting the Three-Fingers Method, one’s intention and mind will be more manifested in writing than the conventional five-fingers methods that are widely used. However, this method is not recommended for beginners or those who do not use the Hanging Arm Technique.

§ 2.5 – Analysis of Methods

Different methods of holding brushes by different calligraphers or theorists serve for particular calligraphy styles and sizes. Generally speaking, a five-fingers method is suitable for larger characters while a three-fingers method is excellent for smaller characters. However, there are no strict rules to use a specific method for a specific style or size. After one has studied and understood theories and principles, the methods can be discerned by the calligrapher’s understanding, needs, insights or preferences. The Hanging Arm Technique is being neglected today; it is also widely used improperly to brag one's skill level. Without doubt, this technique is the most important step in the training of a Chinese calligrapher's skills. If no part of the arm touches the desk, the strength of our whole body can pass through the shoulder, arm, elbow, wrist, and fingers into the brush tip. Only in this way will the strokes be correspondingly more vivid and profound. To attain mastery of this method may require decades of persistent practice, discipline, bravery as well as good eyesight, sound personality, and a healthy nerve system.

Hanging Arm Technique in writing 1"x1" characters

There are many people who start learning Chinese calligraphy later in their life, say after retirement. Some of them assert that it is absolutely impossible for the ancient masters to write characters within 2 x 2 inches with the Hanging Arm Technique because their hands will be trembling in doing such smaller characters. They base their assertions on their physical conditions and calligraphy levels, but not on the conditions of the ancient masters' or those who can write smaller characters with the Hanging Arm Technique today. Some even quoted Su Dongpo's ( 蘇東坡 ) words that he never used the Hanging Arm Technique at all and "to see is to believe." They sometimes question people who believe in the fact that one can use the Hanging Arm Technique to write characters as small as one square inches "Have you ever seen anyone doing that with your own eyes or you just read in the books?"

In reality, there are ways to train the Hanging Arm Technique regardless of age as long as one's hand is not shaking when holding chopsticks or a fork. Children and seniors can start training the Hanging Arm Technique as long as they will let go the mental obstacles rather the physical constraints related to ages. The mental obstacles sometimes come from what we see and what we worry in our mind.

When a practioner has practiced Chinese calligraphy long enough, one may realize that the ancient proverb "A fixed method is not a method ( 定法非法 )" and many ways of holding a brush may be used when one has transcended to a higher skill level - a so-called good or bad method no longer exists. One may realize that one's best way to hold a Chinese calligraphy brush is to make the best of the situations related to many factors.

Last modified: 06/28/2016 (Names changed to Pinyin except for folder and file names)