|

Click to play the entire Playlist of Li Shu Sample Lessons Double

click the video to play in YouTube for

|

Chinese Calligraphy in Li Shu (Clerical Style) 隸 書

Updated: 02/15/2013

|

Click to play the entire Playlist of Li Shu Sample Lessons Double

click the video to play in YouTube for

|

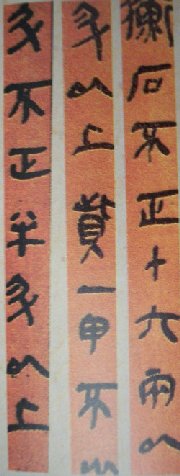

Li Shu germinated in the pre-Chin period ( 先秦時代 ). During the Chin Dynasty it came to be used by low-ranking officials for more prompt government operations. It simplified the more complicated strokes of Zuan Shu and used a bend instead of making a roundabout turn. This is called Chin Li ( 秦隸, Clerical Style of the Chin Dynasty) or Old Li ( 古隸 ).

Chin Li on bamboo rolls

Li Shu is attributed to Cheng Miao ( 程邈 ) who was a prison official in the Chin Dynasty. The script was used by clerks working in prisons, hence the Chinese term Li Shu ( 隸書 ) (literally, servitude script).

By the Han Dynasty Li Shu became popular as a writing style. During the four hundred years history of the Han Dynasty, calligraphers created many beautiful works of Li Shu.

The structural design of Li Shu is somewhat similar to Zuan Shu. Their principles focus on the spacing between strokes. The spacing and position of strokes are well designed to render a sense of elegance and beauty. Compared to Zuan Shu, round edges were squared off and curves became straight in Li Shu.

|

Basic Characteristics and Rules of Li Shu |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note that most of the rubbings from tablets are reprinted as Model Books ( 字帖 ) after they have been cut and pasted by collectors and publishers. So the "Upward Alignment" feature can only be observed from a picture of the whole tablet rather a singe page in a Model Book. A complete view of the Tsao Chuan Tablet with the Upward Alignment However, ancient calligraphers wrote characters more naturally and freely without grids. So there were many Li Shu works that did not follow this “Upward Alignment” preference.

|

|

|

Note in this character “ 不 ” which means “not”, the last stroke is heading southeast and it has to be the Goose Tail. Though there is a horizontal stroke on top, it cannot be the Goose Tail. If the horizontal stroke on top is the Goose Tail, then the last stroke Na will not be a Goose Tail and this won’t make it symmetric with the stroke going diagonally to the southwest direction as the whole character won’t be in balance. Remember in most cases there is only one Goose Tail allowed in a character. The best way to learn about the Goose Tails in characters is from observing the Model Books.

|

Of all the five major styles of Chinese calligraphy, the Clerical Style is probably the easiest to learn. All a beginner has to learn first is the wavelike horizontal stroke ("Goose Tail"). Then one may realize that Na ( 捺 ) is in the variant direction of Goose Tail and Pe ( 撇 ) is the mirror image of Na, also a variant of Goose Tail. Then the easier vertical stroke, Su ( 豎 ), shorter non-wavelike horizontal strokes, and composition of structures are almost self-explaining and intuitive to most learners. In fact, many people can learn Li Shu better in a shorter time than Kai Shu as the requirements of basic strokes in Kai Shu are the most strict from artistic points of view.

The changes and development of Chinese calligraphy styles were in the order of Zuan, Li, Tsao, Hsin and Kai. In fact, Zuan Shu includes several styles (Oracle Bone Inscriptions, Bronze Inscriptions, and etc); Li, Hsin, and Kai are just referring to a unique style respectively.

From the invention of Chinese characters to the Chin Dynasty, Chinese characters had had drastic revolution and changes. However, if we compare the characters during this span with those after the Han Dynasty, differences in characters are found in styles, structure, strokes as well as the writing method and brushwork. Thus the evolution of Chinese characters is usually divided into two main periods: before or after the Chin and Han Dynasties.

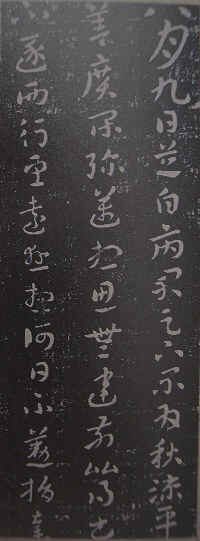

After the Chin and Han Dynasties, the drastic revolution of Chinese characters was focusing on promulgation and convenience of writing. The underlying principles to create a character as set in Zuan Shu were ignored and thus chaos exited for a long time. During this chaos, some characters were written in round shapes and others in sharp rectangle shapes for the sake of beauty. Only after the Han Dynasty, these ways of writing for beauty’s sake were disappearing eventually. However, because of the Chinese nationality, the revolutionists of characters were gradually forming a new style – the Li Style in search for a higher level of beauty and elegance. After the establishment and rise of Li Shu, its use and purpose were greatly different from those of Zuan Shu. During this time, Zuan Shu was used only for important occasions while Li Shu became the main style used in daily life including ceremonies and many cultural events. Thus Li Shu became extremely popular during the Han Dynasty for about 400 years. This kind of Li Shu was also the predecessor of Tsao Shu as seen today. We may find the evidence from Li writing on wood rolls ( 木簡 ).

|

|

|

Zhang Chih’s ( 張芝 ) Tsao Shu retained some qualities of Li Shu. |

A transitional style on wood rolls resembled mixed Zuan and Li Styles. |

Because the main writing style in the early Han Dynasty and the Three Kingdoms Period was Zuan Shu, Li Shu had experienced numerous refinements and changes. Then Li Shu reached its maturity and peak during the later period of the Han Dynasty. The number of Li Shu tablets in the Han Dynasty exceeded other dynasties.

The

Han Dynasty and

the Three Kingdoms

Period were the intertwined periods for the development of the Li, Tsao,

Hsin, and Kai Styles of calligraphy. They were also the periods that Chinese

calligraphy was reaching its maturity. In the Chin

Dynasty, both Zuan and Li scripts were used but Zuan was used only for

important government operations.

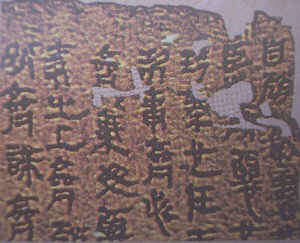

In 1901, Aurel Stein led a group of Indian archaeologists and found 40 pieces of writing on woodsticks called wood rolls ( 木簡 ) . They found more than 1000 pieces in their later adventures between 1906 and 1916. The discoveries of the two volumes of Lao Tzu’s Dao De Jing "The Classics of The Way and Virtue" and other works written on wood rolls were showing the transitions from Zuan Shu to Li Shu. The first volume was written in Small Seal Style (literally Small Zuan) with some Li Shu characteristics; this was estimated to be a work between 206 to 195 B.C. The second volume was written in Li Shu with some Zuan Shu characteristics. These evidences give us clues to understand the evolution of Zuan and Li Styles calligraphy during that period. The later period of the Han Dynasty was also the time that paper was invented and brush pens were improved. Chinese calligraphy theories were also being published and different methods of holding the writing brushes were emphasized. These factors were also closely related to the development of Li Shu.

|

|

|

The Book of Changes written in Li Shu |

Dao De Jing ( 道德經 ) written in Li Shu |

Li Shu writing on woodsticks

A lot of calligraphy teachers agree that students may start learning Chinese calligraphy directly from Li Shu. The basic reasoning is that Li Shu is easy to learn and it can be a preparatory to Zuan Shu. They also agree that students may learn Kai Shu right after Li Shu, or concurrently.

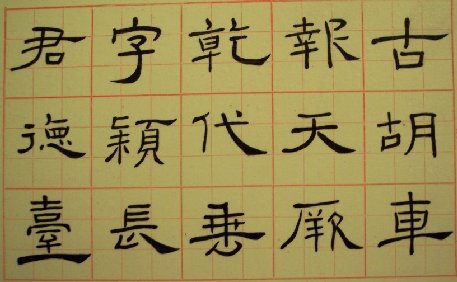

A sample sheet of copying Li Chi Bei on Mao Bien Paper

The principles of brushstrokes are very similar between Li Shu and Zuan Shu. The Center Tip Theory ( 中鋒理論 ) asserts that the brush's handle, hair, and tip not to be tilted during writing. This requirement fit for Zuan Shu as well as Li Shu. Remember this is the core of all Chinese calligraphy theories and it was mentioned by every prominent calligrapher. When Yen Jen-Ching ( 顏真卿 ) stated how his teacher Zhang Shui ( 張旭 ) passed to him the secrets of using a brush, he pointed out that the calligraphy should look like drawing on sand with awl ( 錐劃沙 ). The principle requires keeping our brush and brush hair as straight and vertical as possible. It’s different from Chinese or Western painting, the Western way to hold a pen, and the current Chinese pen or pencil writing.

According to the Center Tip Principle, we should never bend the brush and its hair. We may rotate the brush when necessary with fingertips (knuckles not recommended). Tilting a brush or brush hair outward or toward oneself and sideways during writing is a very common pitfall which can be seen in many pictures on newspapers and the Internet.

By strictly obeying this principle, the hair (and the sharpness of hair) of a brush are hiding inside during brush motions rather than going scattered and collapsed. If one can observe this principle, his/her success in practicing Chinese calligraphy and even Chinese painting can be more guaranteed! (Chinese Brush Painting uses the Center Tip motions as well as sideway motions and many other combinations to create the textures of different objects.)

|

This is a video showing incorrect operation of the brush when writing the Goose Tail. Notice that at the third horizontal stroke (which is the Goose Tail) the brush is tilted. This can be avoided by straightening the brush hair again on the ink stone before writing this stroke.

|

Please refer to the next section to select a model of Li Style to start.

|

Famous Tablets in Clerical Styles

|

||

|

|

Hsi Ping Stone Classics 熹平石經

|

Hsien Yu Huan Bei 鮮于璜碑

|

|

Yi Inn Bei 乙瑛碑

|

Thu Cheng Bei 史晨碑

|

Li Chi Bei 禮器碑

|

|

Thu Meng Sung 石門頌

|

Xi Hsia Sung 西狹頌

|

Zhang Chian Bei 張遷碑

|

|

|

|

Deng's

family was poor when he was young and he could not attend school. He learned

calligraphy and seal carving from his father and literature from the senior

scholars in his town. When he was after twenty years old, he earned a living by making seals.

He traveled extensively to make friends with scholars. When

he was twenty-seven, a chief lecturer of an academy who appreciated his

intellect and talents referred him to Mae Mio ( 梅謬

). Mae was a famous collector

and connoisseur of ancient calligraphy

works of the Chin and Han Dynasties. While staying at Mae’s house for

eight years, Deng Thu-Ru treasured every moment of his time to practice

emulating ancient calligraphy pieces. He learned his Seal Style from the Stone Drum Inscriptions

( 石鼓文

)

and Lee Yang-Bin’s ( 李陽冰

)

work and Clerical Style from the tablets of the Han

Dynasty.

Later

he resumed his travel because of Mae's deteriorating financial status. We he was

forty-eight, he visited Beijing but was not happy there. He traveled again

and received recognition from many scholars. Because

of his poverty and insufficiency of receiving instructions, his works around age thirty were not

highly regarded. 鄧石如原名琰,清仁宗琰,因避字諱,更名石如,字頑伯,自號完白山人、龍山樵人、籍游道人等。白麟畈(今五橫鄉白麟村)鄧家大屋人。是清朝傑出的書法家、篆刻家。 鄧石如出身于清寒書香門第。祖父鄧士沅,是個窮秀才,獨對明史和書畫酷愛。父鄧一枝,善詩文,工書畫,更愛刻石。終年在外教書,難能維持家口溫飽,遂致“枯老窮廬,嘗自悲之”。石如 9 歲隨父讀書,10 歲便輟學,14 歲“以貧故,不能從學,逐村童採樵、販餅餌,負之轉鬻”。然在其祖父和父親的影響下,對書法、金石、詩文發生了深厚的興趣。 17 歲時,為“瀟洒老人”作《雪浪齋銘并序》篆書,即博時人好評。自此,便踏上書刻藝術之路。20 歲在家鄉設館,任童子師,不耐學生“憨跳”而離去,隨父去壽州(今壽縣)教蒙館,21 歲因喪妻辭館,外游書刻,以緩悲痛。 乾隆三十九年 ( 1774 年) 他 32 歲時,復至壽州教書,並常為壽春循理書院諸生刻印和以小篆書寫扇面。深得書院主講梁獻(亳縣人,以善摹李北海書名于世)賞識,遂推荐他到金陵(今南京)舉人梅謬家學習。梅家既是宋以來的望族,又是清康熙御賜翰墨珍品最多的家族,家藏“秘府異珍”和秦漢以來歷代許多金石善本。鄧石如縱觀博覽,悉心研習,苦下其功。在梅家8 年,前五年專攻篆書,後三年學漢分。 鄧石如于乾隆四十七年他 40 歲時,離開梅家,遍游各處名勝大川,臨摹了大量的古人碑碣,錘煉了自己的書刻藝術,“篆隸真行草”皆備。 乾隆四十七年,他游黃山至歙縣,結識了徽派著名金石學家方君任和溪南經學家程瑤田,及翰林院修撰、精于篆籀之學的金榜。後經梅謬和金榜舉荐,結識戶部尚書曹文埴。 乾隆五十五年秋,弘歷八十壽辰,曹文埴入都祝壽,要鄧石如同去,鄧不肯和曹文埴的輿從大隊同行,而戴草帽,穿芒鞋,騎毛驢獨往。 至北京,其字為書法家劉文清、鑒賞家陸錫熊所見,大為驚異,評論說:“千數百年無此作矣。”然而鄧石如遭內閣學士翁方綱為代表的書家的排擠,被迫“頓躓出都”,經曹文埴介紹至兵部尚書兩湖總督畢源節署(署武昌)作幕賓,為畢源子教讀《說文字原》。在署三年,不合旨趣,遂去。 乾隆五十九年他 52 歲時,由武昌回故里,買田 40 畝,翌年建屋一棟,親書匾額“鐵硯山房”置于門首。常將書刻售資救濟鄉人,貧不能葬者,都盡力資助。 之後 10 年,他的書刻藝術越臻化境,不顧年邁,常游于京口(今鎮江)、南京、揚州、常州、蘇州、杭州等地。臨終前一年,還登泰山,會晤友人,切磋技藝。60 歲時,他游京口,結識包世臣,授書三年,以書法要訣示曰:“疏處可以走馬,密處不使透風,常計白以當黑,奇趣乃出。”包以其法驗六朝之書都全符合。 63 歲臨終這一年,仍收錄門生程蘅衫,為篆書《張子西銘》。 是年,得知涇縣有八塊碑需以大篆、小篆、分書、行楷各體書寫,慨然應邀,僅書一碑因病而歸,陰曆 10 月卒于家。山人晚年好友望江知縣師荔扉寫詩哀悼:山人隨鶴化,齊向白雲鄉。金石垂千古,圖書剩一囊。丁令威終返,林和靖已亡。集賢關外路,落葉擁殘陽。鳳台知縣、輿地學家、武進人李兆洛,為鄧石如撰“墓誌銘”,引其生前“教侄書”云:“讀書須極熟,然后得尺則尺,得寸則寸,久之自不能捨。我少時未嘗讀書,艱危困苦,無所不嘗。年十三四,心竊竊喜書。年二十,祖父攜至壽州,便已能訓蒙。今垂老矣,江湖游食, 人不以不識字人相待,暫能讀書,獲益如此,汝輩何不及時自勉哉!父母不足恃,家業不足恃,自己力氣不足恃,可恃者:讀書明理、存心忠厚而己。”

|

|

|

Li Shu Sample Lessons Playlist (new videos will be added eventually)

|

Emulating Shu Cheng Bei ( 史晨碑 ) When practicing and copying from the Model Book, one has to be calm and write in a moderate speed. Rushed pace will not help one to observe the nuances and think into the details of the model; rather it will probably lead one to form into a habit of bypassing many valuable aspects worthy to learn.

Mounting a sheet of copied Shu Cheng Bei ( 史晨碑 )

|

|

Videos with Pronunciations and Explanations of Basic Principles of Li Shu |

|

PLEASE CHECK BACK LATER.

Most calligraphers agree that beginners may start learning Li Shu as their first style. The reason is that Li Shu is easier to learn as compared to the other four major styles. The student should choose a Han Dynasty Li Shu Tablet as their first choice of models. Most Chinese scholars assert that Li Shu Tablets of the Tang Dynasty should not be used as models because Li Shu in the Tang Dynasty was widely considered lack of the simplicity, elegance and nature as compared to Li Shu of the Han Dynasty. (More reasons are in the YouTube video, description, and comments.)

A typical Li Shu work in Tang Dynasty lacks depth and delicacy

After

being familiar with Li Shu, one may proceed to Zuan

Shu. It is quite common that we can refine and edify our Li Shu by

practicing more Zuan Shu, or vise versa. They share some mutual aspects in

theory and many great Li Style calligraphers were also Zuan Style calligraphers.

Great

Seal Style ( 大篆

,

literally Big

Zuan)

–

Chinese characters used in the pre-Chin periods.

Center Tip Theory ( 中鋒理論 ) – Holding a brush vertically but not bent; never tilt hairs during writing.

Chin

Zuan ( 秦篆

)

–

Official and simplified Seal Style in the Chin Dynasty derived from Big Zuan.

Chin

Li ( 秦隸

),

also called Old

Li ( 古隸

)

–

Clerical Style of Chin Dynasty. Early Li Shu as used by the Chin Dynasty prison officials.

Han Li ( 漢隸 ) – Clerical Style of Han Dynasty. Most tablets in the Han Dynasty were written in Li Shu. They were considered the best Li Style works in China's history.

Jade Ligament Seal Style ( 玉筋篆 ) – Nickname for Small Seal Style with thinner strokes.

Lee

Yang-Bing ( 李陽冰

)

–

a famous Seal Style calligrapher in the Tang Dynasty.

Small Seal Style ( 小篆, literally Small Zuan ) – As opposed to Great Seal Style; Zuan Shu developed and modified after the Great Seal Style.

Wood

Rolls ( 木簡

)

–

In the Han Dynasty, Li Shu calligraphy was also written on woodsticks or on

cloth or silk.

The writing sometimes contained some Zuan Shu characteristics in the brush strokes and structures.