Theories of Chinese Calligraphy

The

method of beautiful Chinese writing is called

“Shu Fa 書

法.”

Shu means writing and Fa means method.

We are not sure about how the earliest Chinese characters were written. From archaeological findings, we can see writing with brush and ink in the early civilization of China. Some scholars presume that Chinese calligraphy was started at the same time when Chinese characters were invented.

Early writing with brush and ink on pottery shows evidence of the birth of Chinese calligraphy

The

early Chinese people deeply loved and appreciated beauty. They made writings beautiful

when each character was invented. The innocent beauty and simplicity of

Chinese characters always attract our appreciation and adoration. From

the ancient characters, brush writings in the styles of Zuan, Li, Tsao, Hsin, and Kai

were invented and

enriched with a high level of beauty.

The

Chinese people deeply emphasize and respect methodology “Fa 法”

in many areas such as martial arts, calligraphy, and painting. Chinese seldom value things that are too popular or common.

Chinese

highly respect the methodology derived from writing characters. Thus Chinese

calligraphy was developed and systematically practiced at large. Brush

principles, theories, esthetics, and philosophy were also introduced into

the calligraphy methodologies. The methodologies in

writing are not unchangeable. When they were changed, new methods and Chinese calligraphy

styles were introduced throughout the different dynasties

of China.

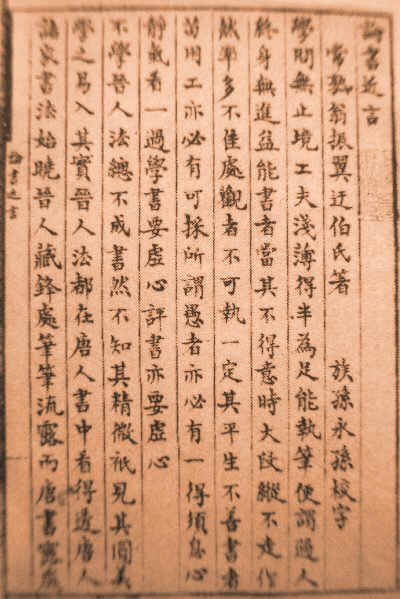

Calligraphy theories were published in each dynasty and they revealed the principles, understandings, secrets, and insight of each calligrapher. The following are a few excerpts from theories published in books and articles. They provide excellent methodologies and insights for studying Chinese calligraphy. Those articles were all written in Classical Chinese Style “Wen Yen Wen 文 言 文” and there are very few English translations available. (More English translations are listed in T2: Excerpts from Essays & Biographies.) By studying these articles, we will benefit from insights and inspiration handed down by the early artists.

The Nine Postures 九 勢: Tsai Yong (132-192) of the Han Dynasty. He emphasized that strength should be kept inside strokes by using Tsun Fong technique. He also pointed out the Ying and Yang attributes of each character’s posture.

Calligraphy Postures of Four Styles 四 體 書 勢: Wei Heng (252-291) of the Jin Dynasty

Section

1: Creation and establishment of ancient Chinese characters

Section

2: From Da Zuan to Tsai Yong’s Zuan Shu

Section

3: Revolutions of characters in the Han and Wei Dynasties

Section 4: Popularization of Tsao Shu since Emperor Zhang Di ( 章 帝 ) of the Han Dynasty

Map of Strokes Disposition 筆 陣 圖: Madame Wei (272-349) of the Jin Dynasty. She was a daughter of Wei Heng and a teacher of Wang Hsi-Chih. She proposed theories about the flow of stroke sequences and fundamentals of calligraphy. She also emphasized the importance of brush, ink and inkstone. There were seven methods of holding the brush summarized in her articles and the respective effects were also discussed.

Discussion on Calligraphy 書 論: Wang Hsi-Chih (307-365) of the Jin Dynasty.

|

王 羲 之 書 論 (傳) Discussion on Calligraphy (presumed to be written by Wang Hsi-Chih) (To be translated) 夫書者,玄妙之技也,若非通人志士,學無及之。大抵書須存思,余覽李斯等論筆勢,及鐘繇書,骨甚是不輕,恐子孫不記,故敘而論之。 夫書,不貴平正安穩。先須用筆,有偃有仰,有欹有斜,或小或大,或長或短。凡作一字,或類篆籀,或似鵠頭;或如散隸,或近八分;或如虫食木葉,或如水中蝌蚪;或如壯士佩劍,或似婦女纖麗。欲書先構筋力,然后裝束,必注意詳雅起發,綿密疏闊相間。每作一點,必須懸手作之,或作一波,抑而后曳。每作一字,須用數種意:或橫畫似八分,而發如篆籀;或豎牽如深林之喬木,而屈折如鋼鉤;或上尖如枯杆,或下細如針芒;或轉側之勢似飛鳥空墜,或棱側之形如流水激來。作一字,橫豎相向;作一行,明媚相承。第一須存筋藏鋒,滅跡隱端。用尖筆須落鋒混成,無使毫露浮怯;舉新筆爽爽若神,即不求于點畫瑕玷也。若作一紙之書,須字字意別,勿使相同。若書虛紙,用強筆; 若書強紙,用弱筆; 強弱不等,則蹉跌不入。 凡書貴乎沉靜,令意在筆前,字居心后,未作之始,結思成矣。仍下筆不用急,故須遲。何也? 筆是將軍,故須遲重。心欲急不宜遲,何也? 心是箭鋒,箭不欲遲,遲則中物不入。夫字有緩急,一字之中何者有緩急?至如“烏”字,下手一點,點須急,橫直即須遲,欲“烏”之腳急,斯乃取形勢也。每書欲十遲五急,十曲五直,十藏五出,十起五伏,方可謂書。若直筆急牽裹,此暫視似書,久味無力。仍須用筆著墨,不過三分,不得深浸,毛弱無力。墨用松節同研,久久不動彌佳矣。

|

|

王 羲 之 自 論 書 (傳) Self Comment on Calligraphy (presumed to be written by Wang Hsi-Chih) 吾書比之鐘、張當抗行,或謂過之,張草猶當雁行。張精熟過人,臨池學書,池水盡墨,若吾耽之若此,未必謝之。後達解者,知其評之不虛。吾盡心精作亦久,尋諸舊書,惟鐘、張故為絕倫,其餘為是小佳,不足在意。去此二賢,僕書次之。頃得書,意轉深,點畫之間皆有意,自有言所不盡。得其妙者,事事皆然。平南李式論君不謝。

|

|

王 羲 之 題 衛 夫 人 筆 陣 圖 後 (傳) Comment on Madame Wei's "Map of Strokes Disposition" (presumed to be written by Wang Hsi-Chih) 夫紙者陣也,筆者刀也,墨者鍪甲也,水硯者城池也,心意者將軍也,本領者副將也,結構者謀略也, 筆者吉兇也,出入者號令也,屈折者殺戮也,著筆者調和也,頓角者是蹙捺也。始書之時,不可盡其形勢,一遍正腳手,二遍少得形勢,三遍微微似本,四遍加其遒潤,五遍兼加抽拔。如其生澀,不可便休,兩行三行,創臨惟須滑健,不得計其遍數也。 夫欲書者,先乾研墨,凝神靜思,預想字形大小、偃仰、平直、振動,令筋脈相連,意在筆前,然後作字。若平直相似,狀如算子,上下方整,前後平直,便不是書,但得其點畫耳。昔宋翼常作此書,翼是鐘繇弟子,繇乃叱之。翼三年不敢見繇,即潛心改跡。每作一波,常三過折筆;每作一點,常隱鋒而為之;每作一橫畫,如列陣之排雲;每作一戈,如百鈞之駑發;每作一點,如高峰墜石;屈折如鋼鉤;每作一牽,如萬歲枯藤;每作一放縱,如足行之趣驟。翼先來書惡,晉太康中有人於許下破鐘繇墓,遂得《筆勢論》,翼讀之,依此法學書,名遂大振。欲真書及行書,皆依此法。 若欲學草書,又有別法。須緩前急後,字體形勢,狀如龍蛇,相鉤連不斷,仍須棱側起伏,用筆亦不得使齊平大小一等。每作一字須有點處,且作餘字總竟,然後安點,其點須空中遙擲筆作之。其草書,亦復須篆勢、八分、古隸相雜,亦不得急,令墨不入紙。若急作,意思淺薄,而筆即直過。惟有章草及章程、行狎等,不用此勢,但用擊石波而已。其擊石波者,缺波也。又八分更有一波謂之隼尾波,即鐘公《太山銘》及《魏文帝受禪碑》中已有此體。 夫書先須引八分、章草入隸字中,發人意氣,若直取俗字,則不能先發。予少學衛夫人書,將謂大能;及渡江北遊名山,見李斯、曹喜等書,又之許下,見鐘繇、梁鵠書,又之洛下,見蔡邕《石經》三體書, 又於從兄洽處,見張昶《華岳碑》,始知學衛夫人書,徒費年月耳。遂改本師,仍於眾碑學習焉。時年五十有三,恐風燭奄及,聊遺於子孫耳。可藏之石室,勿傳非其人也。

|

|

記白雲先生書訣 天臺紫真謂予曰“子雖至矣, 而未善也。書之氣, 必達乎道, 同混元之理。七寶齊貴, 萬古能名。陽氣明則華壁立, 陰氣太則風神生。把筆抵鋒, 肇乎本性。刀圓則潤, 勢疾則澀;緊則勁, 險則峻;內貴盈, 外貴虛;起不孤, 伏不寡;回仰非近, 背接非遠;望之惟逸, 發之惟靜。敬茲法也, 書妙盡矣。”言訖,真隱子遂鐫石以為陳跡。維永和九年三月六日右將軍王羲之記。

|

Article on Zhong Yao’s Calligraphy: Emperor Wu Di 粱 武 帝 (464-549) of the Liang Dynasty. Emperor Wu Di said that there were twelve stages of mind levels with extraordinary wonders within Zhong Yao's calligraphy work. He advised people to learn Chinese calligraphy with methods of higher levels. “ 取 法 乎 上 ”

Secrets & Tips of Emulation: Lu Juan of the Tang Dynasty.

Calligraphy Score 書 譜: Sun Guo-Ting (648-703) of the Tang Dynasty.

Recent Essays on Calligraphy 論 書 近 言: Wong Zeng-Yi of the Ching Dynasty.

“Yi Zo Thuan Ji” 藝 舟 雙 輯: Bao Shu-Cheng of the Ching Dynasty.

“Exemplifying Yi Zo Thuan Ji” 廣 藝 舟 雙 輯: Kang You-Wei of the Ching Dynasty.